America’s Cup: Debunking the myth

Published on March 14th, 2019

We have read the story many times. Of how the schooner America, newly arrived from across the Atlantic in the year of the Great Exhibition, trounced the best of British yachting in a race around the Isle of Wight. And of how her owner, Commodore John Cox Stevens of the New York Yacht, returned triumphant to prove the best of the New World more than a match for that of the Old.

Yet, from the moment she met and supposedly signaled her prowess in an informal race with the Laverock off Cowes, to the apocryphal ‘There is no second, m’am’, her reputation has not stood up to scrutiny. Adrian Morgan offers this report to debunk the myth:

On March 28, 1942, an unusually heavy snowfall smothered the New England countryside. At the height of the blizzard, the roof of a nondescript shed on the waterfront at Trumpy’s Yard in Annapolis collapsed. The incident was scarcely newsworthy. America was at war and had other, far more pressing, matters on its mind.

But to the historians of the America’s Cup it was a tragedy, for the shed was the final resting place of a low, black schooner whose legacy has inspired controversy ever since. Nearly 80 years after the world’s most celebrated yacht was crushed beneath tons of corrugated iron and snow, the myth of her invincibility still endures.

America was designed by George Steers, superintendent of the mould loft at the yard of New York’s leading shipbuilder, William H Brown, at the foot of 12th Street on the East River. Steers’ father had learned his trade at the Royal Naval Dockyard at Devonport, immigrating to the United States in 1819, a year before George was born.

Brown agreed to build a ‘strong, seagoing vessel, and rigged for ocean sailing’. The schooner’s lines were a development of Steers’ earlier 66ft pilot schooner Mary Taylor, built in 1849, which had established the 31-year-old designer’s reputation.

With a hollow entry and carrying her maximum beam of 22ft well aft, America measured 101ft 9in overall on a waterline length of 90ft 3in. On her steeply raked 79ft 6in foremast and 81ft mainmast she carried a simple rig: jib, foresail and mainsail, totaling 5263 sq ft, cut by Rubin H Wilson of Port Jefferson, Long Island, New York from cotton duck woven at Colt’s Factory in Paterson, New Jersey.

America was commissioned by a syndicate headed by Commodore John Cox Stevens of the New York Yacht Club specifically to take up a challenge proffered by Lord Wilton of Grosvenor Square, London, commodore of the Royal Yacht Squadron in a letter dated February 22 1851, the year of the Great Exhibition.

In his reply, Stevens wrote: “…some four or five friends and myself have a yacht on the stocks, which we hope to launch in the course of two or three weeks. Should she answer the sanguine expectations of her builders, we propose to avail ourselves of your friendly bidding, and take with a good grace the sound thrashing we are likely to get by venturing our longshore craft in your rough waters…”

The price agreed for her building was high – $30,000 – but extraordinary conditions were written into the contract. If she did not prove to be the fastest vessel in the United States the syndicate could refuse her. Moreover, if she was to prove unsuccessful in England, her builders would be obliged to take her back. Stevens, a wealthy man and notorious gambler, was taking no chances. He meant to cover his bets either way, even if America turned out to be hopelessly outclassed.

A variety of woods were used in her construction: the frames, braced by iron diagonals, of white oak, locust, cedar, chestnut and hackmatack; her planking, copper fastened, of 3in white oak; her decks of yellow pine and her coamings of mahogany. She carried 61 tons of iron ballast, two thirds of it under the mainmast.

Her launch date was set for April 1, but bad weather delayed it until May 3 and it was June 18 before she was finally ready to sail for England. In the meantime the astute Stevens had driven the price down to $20,000 after inconclusive trials against Stevens’ own fully-tuned up 97ft sloop Maria, to which she owed time, designed by his brother Robert.

On one occasion Maria sailed three circles around America. “As far as the trials went,” wrote George Schuyler, a syndicate member ‘the Maria proved herself faster…’

On June 21, with her racing sails stowed below, she was towed to Sandy Hook. During the course of her Atlantic crossing she was to make several 200-mile-a-day runs and one of 284 miles. James Steers, George’s older brother, was impressed. On 27th June, he wrote: “She is the best sea boat that ever went out of the Hook.”

Steers, his brother, young nephew and 10 crew arrived off Le Havre after a 20-day passage. There she was repainted, her masts restepped and her racing canvas carefully bent on.

Despite the entreaties of Horace Greeley, a New York newspaper editor in Paris, who predicted that “You will be beaten, and the country will be abused,” after three weeks refitting, and in thick fog, Stevens, who had taken the steamer to Le Havre, and his crew sailed for Cowes.

Greeley’s departing words, would, no doubt, have been ringing in their ears: “Well, if you do go, and are beaten, you had better not return to your country!”

The crack British cutter Laverock found her early on the morning of August 1 anchored off Osborne House, five miles from the entrance to the Medina River, waiting for a breeze. The story of that informal race is often given as the first evidence of America’s invincibility.

Like any other two racing yachts sparring for an informal race, the tensions aboard were electric. “After waiting till we were ashamed to wait any longer,” said Stevens describing the meeting at a dinner given in his honour at Astor House later that year “we let her go about two hundred yards, and then started in her wake… Not a sound was heard, save perhaps the beating of our anxious hearts or the slight ripple upon our sword-like stem… The men were motionless as statues… The Captain was crouched down upon the floor of the cockpit, his seemingly unconscious hand upon the tiller…”

Seven miles later, America had, allegedly, worked out a handy lead and the myth of her prowess gathered its unstoppable momentum. “The crisis was past, and some dozen of deep-drawn sighs proved that the agony was over,” recalled Stevens. Stevens neglected, however, to mention that Laverock was towing her longboat. The Bell’s Life report on August 3 stated that Laverock “held her own.”

The news of her informal ‘victory’ spread like wildfire. Those who might ordinarily have engaged in a little flutter over the Yankee schooner shied away. In those days huge sums were wagered on yacht racing. In one 224-mile Channel race some £50,000 changed hands.

Stevens was probably more worried about the Laverock race that he cared to admit, for when he did challenge the Squadron, it was to be a schooners-only race, over an offshore course and in over 6 knots of wind. There were no takers.

He then made it known that he was willing to race any ‘cutter, schooner or vessel of any other rig’, but the stake was to be an outrageous 10,000 guineas, more than double the cost of her building: ‘a staggerer’, according to James Steers’ huge even by the standards of a notorious gambler like Stevens.

Historians have tended to read this as evidence of Stevens’ faith in his schooner. If Bell’s Life’s account of the Laverock race is to be believed, may it not have been designed to frighten away competition, leaving Stevens to claim, as the papers would say, that British yachtsmen were, indeed, running scared and allow him to return home reputation intact?

Not surprisingly there was again no response. For two weeks America lay at Cowes, sails furled. Hopes of a race with Joseph Weld’s Alarm, for a purse of $5000, came to naught and the British press, sensing a good story, were scathing.

The Times wrote: “Most of us have seen the agitation which the appearance of a sparrow-hawk on the horizon creates among a flock of wood-pigeons or skylarks when, unsuspecting all danger and engaged in airy flights of playing about over the fallows, they all at once come down to the ground and are rendered almost motionless with fear of the disagreeable visitor. Although the gentlemen whose business is on the waters of the Solent are neither wood-pigeons nor skylarks, and although the America is not a sparrow-hawk, the effect produced by her apparition off West Cowes among yachtsmen seems to have been completely paralysing… It could not be imagined that the English would allow an illustrious stranger to return to America with the proud boast that she has flung down the gauntlet to England and had been unable to find a taker.”

Eventually Stevens’ friend, George Robert Stephenson, son of the railway engineer, offered to race his unremarkable 100 ton Titania, designed by Wave Line theorist John Scott Russell, over a 20-mile windward leeward course for £100. The date was fixed for August 28.

In the meantime the Royal Yacht Squadron, stung by the criticism, took the plunge. When finally America did manage to compete, it was to be for a 27in high cup, crafted by Garrard in High Renaissance style of 134 ounces of silver, worth 100 guineas, subscribed to by their members.

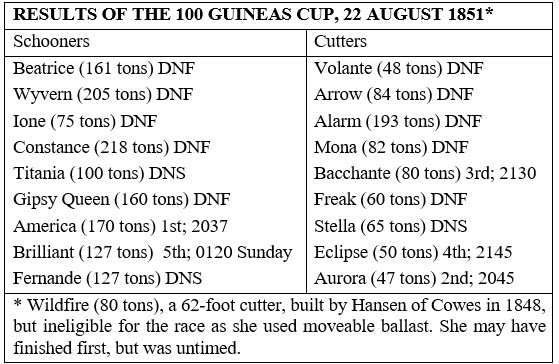

The race, 53 miles around the Isle of Wight, was scheduled for August 22. A south westerly, aided by a strengthening east-going tide, prevailed that morning. No one had any doubts about the outcome.

A Bell’s Life correspondent had reported that the Le Havre pilot, seeing her for the first time in Le Havre, had called her ‘a wonder’ and The Illustrated London News a “rakish piratical-looking craft whose appearance in bygone days in the Southern Atlantic would have struck terror into the souls of many a homeward-bounder…” Betting was heavily in favour of the Yankee schooner.

The fleet, when it finally assembled in two lines off Cowes, must have been apprehensive – and the press, assiduously stoking the fires, had already written their headlines. After the race, as the fleet headed for the Nab, Steers was to complain that the British yachts had tried to form an impenetrable barrier to America’s progress. For such a competitive fleet to have acted thus in harmony must have meant they felt they faced a threat. But did they?

Then and now the accepted wisdom holds that America was revolutionary.

“All in all,” wrote Ernle Bradford in ‘The America’s Cup’, published by Country Life in 1964, “with her simple rig and rigging, her beautiful hull, and her well-fitting sails, the America was a revolution in yacht building.” John Rousmaniere in his excellent The Low Black Schooner, published by Mystic Seaport called her “breakthrough technology.”

GL Watson, designer of Britannia, Valkyrie and Shamrock II believed that half her secret was the use of flat-cut, machine-woven cotton sails, and in stark contrast to the baggy loose-footed flax sails used by the British which needed dowsing with water to make the luff set tight and hard.

“I was on board a steamer on the weather board of the America,” wrote Captain Mason, RN in The Times “and it became a question among us as to whether that vessel had any mainsail set or not, and which I could not discover with the aid of a spyglass. So completely was the sail covered by the mainmast that not a particle of it was visible; there was no belly, and the gaff was exactly parallel with the boom.”

Lord Uxbridge, later the first Marquis of Anglesey, founder of the Royal Yacht Squadron, had other ideas. He even went so far as to accuse America of using a propeller. At Waterloo he had commanded the cavalry division and was on his horse beside Wellington when a shell took away his leg, prompting the immortal words: “By God. I have lost my leg.” To this the Iron Duke replied “Have you, by God!”

Whilst searching for the offending propeller Uxbridge had to be dragged back over America’s bulwarks by his wooden leg. Eventually he concluded that her secret was hull shape. “I’ve learned one thing,” he said. “I’ve been sailing my yacht stern foremost for the last twenty years.” But had he?

Thus was it was taken as gospel for a century that America was revolutionary; that her sharp, lean, concave bow and wide stern, as against the cod’s head and mackerel-tailed British yachts, and flat cotton sails were superior. After all, had she not comprehensively beaten 15 of Britain’s top racing fleet? Had not the Queen herself, aboard Victoria and Albert off the Needles been told: ‘There is no second, ma’m’? And later, in her second, and last race, under Stevens’ ownership, had she not trounced the 80ft schooner Titania by 52 minutes over a 40-mile course round the Nab light vessel?

The details of America’s victory are still clouded in mystery. Then, as now, the relative positions of the yachts depended on eye-witness accounts, none too reliable. Those newspapermen who did follow the race were aboard a steamer, shadowing America. After America passed the Royal Yacht, with the Queen aboard, off the Needles at around 5.30pm, most of the press had made up their minds and were fretting to meet deadlines.

At that stage Mr Le Merchant’s little 47-ton cutter Aurora was assumed to be at least eight miles behind and clearly out of the race. In fact Aurora was to finish soon after America; 18 minutes behind, according to Bell’s Life and 8 minutes in The Times, the official margin. And in the crush of spectator boats at the finish no one noticed the arrival of the 62ft cutter Wildfire, although an unofficial starter, the only yacht to have sailed the same course as America, inside the Nab Light vessel.

In the crush to record America’s historic meeting at the Needles with the Queen, could the newspapermen have missed the Wildfire, by then setting downwind sails for Cowes? Did they assume that another little cutter just 18 minutes astern of America was the disqualified Wildfire?

This would explain the observation that: “For an hour after America passed the Needles we kept the Channel in view and there was no appearance of a second yacht.” How else could Aurora finish only 8 minutes astern of America and not have been detected at the Needles?

That the press were guilty of wishful thinking and that both Aurora and Wildfire gave superb accounts of themselves are two of the conclusions arrived at by AE Reynolds Brown in a slim pamphlet entitled The Phoney Fame of the Yacht America and the America Cup, published in 1980. Mistaken identity, sloppy reporting and downright manipulation of the facts were among his accusations.

After a late start due to her overrunning her anchor, America had been lying fifth behind Beatrice, Aurora, Volante and Arrow at No Man’s Buoy and was anxious to catch up by any means. All the yachts except America headed for the Nab Light Vessel, (although this has been hotly disputed by historians, some of whom claim as many as six others followed America).

America’s local pilot, Mr Underwood, must have known the accepted practice at the Nab. Instead he set America on a fast reach, close inshore, for Bembridge Ledge, closely followed by Wildfire. From Bembridge to St Catherines the fleet was hard on the wind, bucking a strong tide.

At sundown Wildfire was level. At Dunnose, according to America’s log, Aurora may also have caught her. At St Catherines Wildfire, according to The Times, was three miles ahead of the fleet and was not overhauled until Freshwater Bay.

If Brown is correct, then he would claim by an analysis of wind and tide that America had stood to gain one hour 20 minutes or 8 3/4 miles at St Catherines by her ploy at the Nab. Whatever the truth, observers at St Catherines had timed Aurora just ten minutes astern at that point with Wildfire leading America by 14 minutes.

Brown has no quarrel with Underwood, after all, there was nothing in the race instructions about rounding the Nab. He seeks only to prove that America was not the vaunted race horse she has been made out and that the race and her subsequent, less than illustrious, career proves her to be no better, and arguably worse, than the British yachts she is claimed to have outclassed so comprehensively.

“America was a 90ft schooner and in a 50-mile race round the Isle of Wight, she finished 8 minutes ahead of the 57ft cutter Aurora, so by modern rules Aurora beat her by about 30 minutes on time allowance,” he writes.

Montague Guest in his Memorials of the Royal Yacht Squadron, published at the turn of the century writes: “… the conclusions so willingly arrived at by contemporary yachtsmen as to the superiority of the America were a little hasty. In the first place, as we have said, any application of the tonnage rule even then accepted would have given the Cup to Aurora. Again, the incident of the mistake about the Nab light being included in the course severely handicapped some of the more dangerous of her opponents.”

Under American rules America rated 170 tons; in England 209. Her two greatest threats, Mr Joseph Weld’s 193-ton cutter Alarm and Mr Chamberlayne’s 84-ton cutter Arrow retired early, the former going to the help of the latter, hard aground off Ventnor. One account even puts Volante ahead of the Yankee when she and Freak collided off Ventnor. This left only Aurora of the first class yachts still racing.

Reynolds Brown, after exhaustive tidal calculations and eye witness reports, believes that Aurora was no more than 2 1/4 miles behind America at the Needles, and certainly not 7 1/2 as reported in the Times. In the haze, and with the excitement of America’s meeting the Queen, perhaps no one noticed her. Maybe they ignored her, or mistook her for the disqualified Wildfire.

To have come from nearly 8 miles behind to finish off Cowes only a mile adrift, Aurora would have needed to average nearly 8 knots over the remaining 13.4 miles to Cowes, against a foul tide, yet the wind, by all accounts, was too light for that to have been possible.

Reynolds believes that the press wrote their story too soon. In the haste to find a rod to whip the yachting establishment back, they were guilty of a certain economy with the facts. Reynolds also believes that the times of the tides were manipulated to back up the newspapermen’s story and cover up there incompetence.

What no one mentioned was that Wildfire, the only yacht to have followed America’s course inside the Nab, may well have beaten them all. She may have carried a gang aboard to shift the 2 to 3 tons of ballast – no more than 4% of her 80-ton displacement – to windward but would almost certainly not have bothered in the short tacking underneath the Island and not off the wind.

If she did beat America and if the little Aurora, despite sailing the extra distance out in the tide at the Nab, finished only a mile behind where was America’s vaunted speed. What might have happened had Arrow, Volante even the elderly Alarm, half the vessel she was after a rebuild, stayed clear of trouble?

“The stranding of the Arrow, and the retirement of the Alarm which it entailed, removed two of the most formidable cutters afloat at the time… One has only to think of the relative merits of the Alarm and the Aurora, which ran America so closely, to be convinced of the luck of the America in finding Mr Weld’s great cutter so early out of the race,” concluded Montague Guest.

America was built to Englishman Scott Russell’s Wave Line theory, first employed in the steamer Wave in 1835, as interpreted by the American John Griffiths under whom Steers brother worked. Russell described her ‘a pure wave line vessel’ and reveled in the acclaim.

Influential at the time, it was a flawed theory. “At all speeds,” writes Reynolds Brown “the bow is too sharp and hollow, and the master section too far aft… Dixon Kemp said the America was the only Wave Line yacht that got a reputation for speed. He analysed the lines of a lot of yachts built between 1870 and 1890 but no fast one conformed to it.” By 1880, Russell’s theory had been discredited.

By the standards of the day America was a stripped out racing machine, able to carry only the barest provisions. On her voyage across the Atlantic some of the water for her crew had to be stowed on deck. In contrast Czarina, built by Camper a few years earlier, had stowage for three months stores. America had only 2/3 of her useful space and a far smaller area of full headroom.

Any criteria used to handicap the fleet would have resulted in defeat, which is why Stevens wisely insisted on a straight race. As for her sails, British sailmakers had been experimenting with flat cut flax sails for 20 years. Indeed when the 10 tonner Madge was shipped to New York in 1881 many of the local yachts replaced their cotton sails with loose footed flax ones, so successful did they prove. When America was refitted in 1859, she too was given a suit of flax sails.

Following America’s victory, Stevens made no strenuous effort to seek further competition, crying off on several occasions with various excuses. He must have been relieved that the one match he could not duck, a friendly match with Titania, was against a schooner regarded by all expert opinion as being out of her league.

After the match Stevens was desperate to sell her, but there was no rush to buy at his inflated price. When a gullible punter appeared in the shape of a 39-year-old army officer, John de Blaquiere, fourth Baron of Ardkill, a man with little sailing experience, Stevens could not believe his luck.

He took the money – £5000 – and ran. After taking all expenses into account, Stevens had made a modest profit on his adventure. America, through considerable luck, had emerged from her ordeal in profit and with her reputation intact, though hardly tested.

If de Blaquiere hoped to clean up in the Solent he was to be disappointed. After an 8000-mile cruise, during which she again confirmed herself as a superb sea boat, she returned to race in the Solent. Some accounts say she had her masts cut down by 5ft, but this was not the case. At Leghorn an American, John Winthrop, reported that the only alteration made was the addition of stanchions and lifelines.

RD Burnell in his Races for the America’s Cup, published by MacDonald in 1965, repeating an earlier account by Herbert Stone and William Taylor in their The America’s Cup Races, published in 1958 by Van Nostrand, claimed that she was cut down. This would have made no sense. In no way was she over-canvassed to begin with.

Nor did she race with old sails, another excuse made for her poor performance under her new owner. Her racing sails, hardly worn out after 100-miles of competition in light airs, would have been carefully set aside during the cruise.

In 1852 she raced for the Queen’s Cup. Mosquito, a 60ft cutter built in 1848, beat her. Alarm and Arrow were to do the same. In her last race under Blaquiere’s ownership she trounced Sverige, built expressly to challenge her, but only after the Swedish schooner, leading by nine minutes after 20 miles, carried away her main gaff. Once again the little Wildfire, with her swarthy band of ballast heavers aboard, turned up like an uncouth guest at a society wedding and again crossed the line ahead.

Blaquiere sold her in 1853 and by 1859 she was found to be rotten. At Pitcher’s Yard at Northfleet on the Thames the affected timbers were replaced by English oak. It was there that Reynolds Brown believes her masts were cropped. Two years later she was sold to a Mr Decie and renamed Camilla.

At Cowes in 1861 she was soundly beaten by the 20-year-old Alarm, lengthened and newly converted to schooner rig. She then won a race off Plymouth, and sailed to the West Indies. A year later, under the name the Memphis, she appeared under the Confederate flag in Savannah as a blockade runner. On one occasion she ran ‘clear away’ from the frigate Wabash.

In April 1862 the US gunboat Ottawa discovered her scuttled in St John’s River, her masts barely protruding above the water, her hull full of augur holes. She was refloated and handed over to the Annapolis Naval Academy.

Six years later, crewed by midshipmen from the Academy, she was among the fleet of the America’s Cup’s first defenders, finishing fourth, in front a James Ashbury’s Cambria. In 1876 she finished 19 minutes ahead of a hopelessly outclassed Canadian challenger.

Her last appearance on a course that bore her name was during the Vigilant/Valkyrie matches in 1893 when she took a party of sightseers to watch the action off Sandy Hook. She lay in Boston Harbour from 1900 until 1916 and in 1920 very nearly ended up as a Portuguese trader in the Cape Verde Islands. Too late, for by then the clouds of war were gathering, she was appreciated as a national treasure and efforts were made to raise the funds to restore her. They failed and on the night March 28 1942 she was lost to the elements forever.

In the 20 years following her triumph off Cowes she had sailed only six races. On this scant evidence her reputation is based. There is no doubt that she was a superb sea boat, weathering a memorable storm off the coast of France. Her transatlantic crossing was not only the first but one of the finest and fastest ever, but it is as an inshore racer that her reputation must be judged.

Many subjective comments were made about her prowess, mostly by non-experts of members of the press. Yacht designers conspicuously failed to follow her lead. The Wave Line theory was subsequently proved to be a blind alley.

Commodore Stevens was fortunate to have come home in profit and his reputation intact. By rashly giving in to the urge to race Laverock that summer morning in 1851, historians say he may have kissed goodbye to a fortune.

More likely he discovered America’s Achilles heel and, like the good gambler he was, sought to cover it up by setting an absurdly high stake which he guessed rightly that no one would cover. With the help of a sympathetic press America laid the firm foundations of the myth of speed that survives to this day.

A fast schooner, certainly. In the hands of her New York pilot skipper and Yankee crew she was sailed superbly, but her main competitors self-destructed in the heat of competition and she sailed without time penalty. She was unquestionably great, for she lent her name to the oldest sporting challenge in history. Only the myth of her invincibility fails to stand up to close scrutiny.

We’ll keep your information safe.

We’ll keep your information safe.